This is the story of where the Yorkshire name of 'Hearfield' came from.

Parish records show individual Hearfield families living in the Forest of Knaresborough in the 16th century, but I think the name originated in a small lead-mining area a little further up the Nidd valley ...

Greenhow Hill

Pateley Bridge is a small Yorkshire town in Nidderdale, about ten miles north-west of Harrogate. The river Nidd has cut a steep-sided valley into the rock, and with almost no flat land in the valley bottom the town has been forced to grow up the hillside.

People have been living here for many hundreds of years, even though 'the town contains nothing remarkable' wrote John Byland rather patronisingly in 1815. It does now - the Nidderdale Museum houses an astonishing collection of objects. Pateley Bridge is not specifically mentioned in the Domesday Book (though nearby Bewerley is) but the town received its charter, allowing a weekly market to be held, as early as 1319. The town is linked by road to Otley, ten miles away to the south, and to Ripon, ten miles east. These roads join near the top of the narrow high street and the traveller descends (carefully, as the road is only just wide enough for two cars to pass each other) to the bridge at the bottom. There has been a river crossing here since pre-Roman times. The original ford was replaced by a wooden bridge in the 16th century, which was in turn replaced by the present stone bridge in the 18th century.

It is not immediately clear why many people today should want to cross the river here. Going west out of Pateley Bridge the road climbs steeply up the hillside and continues to rise until it reaches the village of Greenhow on Bewerley Moor. Cyclists should beware, as

... the gradient is exceedingly steep. During the mild winter of December 1905, Miss Elwell, daughter of the vicar of Greenhow, was cycling down this road when she fell, and unfortunately received injuries that resulted in her death.

Halliwell Sutcliffe described the view from the top like this:

[Greenhow Hill's] flowers ... hide surprising beauties among crannies of the walls, or in the furrows of grim rocks, or thrive in boglands where men's' feet seldom stray for fear of sinking. And what of Greenhow's outlook on the world below him? The great ghylls stretch, sheltered and stream-fed, as far as his eyes can travel. Seen close at hand - not far-off from Simon's Seat - the crimson moors are big enough to warm the whole land at their fire. Nothing but mist can hinder Greenhow from seeing how it fares with Whernside, Buckden Pike, Penyghent and Ingleborough; and when he tires of Yorkshire mountains, he can glance aside with a hope of glimpsing Westmorland.

And from Greenhow, the road over the moors gives a pleasant drive on a summer's day through empty landscapes as it gradually descends back down over the moor to Grassington. There is little traffic, and today this road has no obvious purpose.

But a road always has a purpose. The land beneath Greenhow Hill, from Pateley Bridge to Grassington, is threaded with the tunnels of lead mines which fell into disuse a hundred years ago. The land around here has been mined for at least two thousand years. Two pigs of lead have been found, each weighing as much as a man, marked to show that they were cast in the Emperor Domitian's seventh term as consul (that is, in 81 AD) and the word 'Brig' (for 'Brigantes', the tribe then in possession of the region). In 1365, ten tons of lead from Nidderdale was sent south to roof Windsor Castle. Lead was an essential material, for water pipes, for waterproof roofing, for the pigment in paint, and - later - for bullets.

The men who actually dug out the lead-bearing ore did not live close to the mines where they worked. The village of Greenhow didn't exist until the sixteenth century. Crops can't grow on top of the bleak moor, which is lashed by rain in winter and always too cold. Instead, the miners walked three or four miles up the hill to work in the mornings from the settlements of Bewerley and Heathfield, which were the only nearby villages to be listed in Domesday.

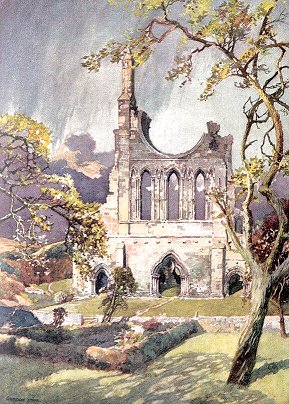

Byland Abbey

Heathfield and the surrounding region belonged to Byland Abbey for several hundred years. This came about not because of some pious benefactor, but as the settlement of a long-running legal dispute.

By the 12th century this land was in the hands of a young man named Roger de Mowbray. The angry lion on his shield indicates what sort of men his ancestors had been, and by now his family held

... not only all the land and its mineral wealth, but all hereditary powers and rights over the lives and properties of the inhabitants and their descendants, born and unborn [in Nidderdale ... but also] 140 Knights Fees in England and 140 in Normandy, together with other valuable possessions ... extending from the Hambleton Hills (including the fertile Vale of Mowbray) westwards to the borders of Northumberland.

Roger used the Nidd valley as a hunting reserve. He lived with his mother in a castle near Thirsk.

One day in about 1138, the castle was visited by a little group of monks with a hard-luck story to tell. They belonged to the Abbey of Furness, of the Order of Savigny, over on the west coast, and had been sent from there to set up an outpost a couple of dozen miles to the north. They had cleared some land for crops and put up wooden buildings. Their Order demanded a strict vegetarian diet - no meat, eggs, or dairy products, unless they fell ill - and coarse clothing. They worked in silence, and slept on straw.

This peaceful little settlement survived for just four years before disaster struck. They were discovered by a raiding party of Scots, who burned the buildings and crops and stole whatever they could find. The monks had trooped back home, disconsolate. But Gerold, their former Abbot, could not tolerate his demotion back to the ranks, and he decided that they must try again somewhere else. They were on their way to York to seek the help of the Archbishop in finding a suitable site when by chance they had met the Mowbray's steward.

Roger's mother was moved to pity. She sent them to a relative of hers, a former Benedictine monk who was living as a hermit a few miles from Thirsk, and they moved in with him. The hermit may initially have resented this invasion of his solitude, but he did join their order.

The monks quickly outgrew their new home, and this time Roger gave them some land on the opposite side of the river from the newly-built Cistercian Abbey of Rievaulx, together with the income from the vill of Byland to support them. Perhaps he thought that the two sets of monks would be company for each other, but if so he was wrong. Each house had fixed ideas as to when services should be held, and summoned its members to prayer by ringing the bells. Unfortunately, the Abbeys held their services at different times, and since the bells of each Abbey were clearly audible to the monks in the other, both houses became increasingly confused and annoyed. It was not to be endured. Once again the monks of Byland (as they were now known) packed their bags and moved. The ever-generous Roger found them another site some five miles to the south, and here they rebuilt their Abbey, this time in stone.

Savigny, their previous Order, had by now been the subject of a successful take-over bid, and Byland Abbey too became a Cistercian house.

Knowing that the Cistercians were charged by their Order to live on the most unfavourable land and cultivate it, Roger gave the monks pasture for eighty mares and their foals within the Forest of Higrefeld - that is, on his land north of Pateley Bridge. Traces of this first grange survive today on modern maps as Colt Plain and Colt House.

He followed the gift with the offer of sufficient land in the Forest to maintain thirty sows and five boars - but for this the monks would have to pay him the rent of a silver mark each year. The Forest was still his private hunting reserve, and the monks were forbidden to do anything which might harm the deer, such as allowing large savage dogs to roam unchecked. Little dogs would be permitted.

By this time Roger had two sons, whom he had named Nigel and Robert. A new crusade was being planned and, like their contemporaries, the boys wanted to go over and teach Salah al-Din's warriors the important Christian virtues of love and forgiveness by chopping them to bits. So Roger needed money. Byland Abbey was flourishing and Roger, who had been their initial benefactor, turned to the monks for a loan. The deal they agreed was that Roger (and his sons) would borrow three hundred marks of silver from the monks for a period of ten years. In exchange, the monks would receive a mortgage on a specified part of the Forest, paying a nominal half-mark in rent each year, and if at the end of the ten years the whole sum (less five marks) was not repaid , the monks could keep the land until it was repaid.

Ten years passed, and the debt was still outstanding. Then Roger died, and eventually his son Nigel died too, and even then the monks did not get their money back. There was a succession of lawsuits, some won by the Mowbrays and some by the monks, and the legal wrangling continued for a hundred years.

Then in 1251, another Roger de Mowbray - a descendant of the man who had incurred the debt - decided it was time to settle things once and for all. He gave the monks a charter which effectively handed over the whole parcel of land - all 27,000 acres - to their ownership in exchange for a one-off payment of a hundred marks. They could do what they liked with it, so long as he retained the right to hunt game there.

The charter also included a clause that exempted the monks from the obligation to entertain Roger, or his heirs or successors, ever again, in any of the Abbey's houses. Even Christian charity has its limits.

'Higrefeld' to 'Heathfield'

Before the Conquest, the village then known as 'Higrefeld' was controlled by Gamel, a local chieftain. He may have been the Gamel who was killed by Earl Tostig for daring to complain about high taxes, but the name was not an uncommon one at the time. Domesday says

Lands of Berenger de Todeni. Manor. In Higrefelt, Gamel had two carucates to be taxed. Land to two ploughs. Berenger now has it, and it is waste. Wood pasture one mile long and half broad. The whole manor one mile long and one broad. Value in King Edward's time twenty shillings.

After England had submitted to his rule, William the Conqueror naturally rewarded his men by giving them the lands of their defeated enemies. The area from the Nidd west to the high moors, and from the stream above Pateley Bridge (which I think used to be known as Foster's Beck but on modern maps is labelled Ashfold Side Beck) to How Stean Beck, up past Middlesmoor at the head of the valley, was disposed of as one parcel. It went to a man named Berenger de Todeni (or Tosny), a member of the powerful land-owning family that built Belvoir Castle, in Leicestershire. I've pieced together the story of what happened later mainly from the accounts given by Harry Speight and William Grainge.

The land around Higrefeld wasn't worth much - the rich veins of lead ore beneath it were not considered very important. After Berenger died, this few thousand acres passed to his nephew's brother-in-law, the warrior bishop Geoffrey de Mowbray. Geoffrey was rich. He already controlled nearly 300 manors up and down the kingdom, a tribute to his bravery in fighting beside William at Hastings as much as to his piety (or shrewdness) in assisting at William's coronation. Geoffrey had an important role in the ceremony - he was the one who solemnly asked the English people assembled in Westminster Abbey whether they would accept William as King. When they yelled back that they would, the guards outside the Abbey panicked at the noise and assumed that the new King was under attack. They reacted by setting fire to the surrounding buildings. Perhaps they thought this would help.

After Geoffrey died in 1093, the whole of his estate went to his nephew Robert de Montbray, the Earl of Northumberland. William I had died a few years earlier, leaving his three sons well provided for. Essentially, William Rufus got England, Robert got France and Henry inherited enough money to do whatever he liked. Rufus was not the man his father had been, and quickly became disliked and then detested by many of his people.

After Geoffrey died in 1093, the whole of his estate went to his nephew Robert de Montbray, the Earl of Northumberland. William I had died a few years earlier, leaving his three sons well provided for. Essentially, William Rufus got England, Robert got France and Henry inherited enough money to do whatever he liked. Rufus was not the man his father had been, and quickly became disliked and then detested by many of his people.

Robert de Montbray decided to act. He rebelled against the hated William Rufus, and when Rufus marched north to sort him out, Robert took refuge in his castle at Bamborough with his wife Matilda. The castle failed to yield to a siege. Rufus lost patience and went off to fight the Welsh instead, leaving behind a small detachment to keep an eye on things.

One night Robert tried to sneak out of the castle in disguise, but he was recognised and captured. The soldiers sent a message to the king asking what they should do with him. Rufus knew that it was imperative for him to capture the castle, which still held out even though its owner was his prisoner. He chose as his weapon a particularly nasty form of blackmail. He ordered that the soldiers should parade Robert in front of his own castle walls, and then put out both his eyes unless his wife Matilda agreed to surrender. She gave in. Robert was stripped of his possessions and spent the remaining thirty years of his life a prisoner.

William Rufus was murdered soon after that. The crown passed to his brother Henry, known as 'Beauclerc' (or 'The Handsome Scribbler', or perhaps even 'The One With The Nice Handwriting'.). In due course Henry arranged to pass on Robert's lands to Nigel d'Albini (or d'Aubigny), Robert's nephew, as a reward for his gallant military service.

Nigel, ironically enough, had just distinguished himself by capturing a castle. Newly rich, he looked around for a wife, and decided that the woman he wanted most in all the world was - his aunt Matilda! Of course, he needed the Pope's explicit permission to marry a woman whose husband was still alive, even though he was in no position to stop them. But the marriage didn't last. It ended officially when he suddenly remembered that he and his aunt were relatives, and so the wedding had obviously been unlawful.

After a while, the king took him on one side and suggested that he should marry a nice young woman called Gundreda, and whilst he was about it, he should change his name to Mowbray. He took the advice. Gundreda bore him two sons.

When Nigel de Mowbray died, his elder son Roger inherited vast estates in Normandy and Lincolnshire, together with odds and ends including the few thousand desolate acres above Pateley Bridge. Roger liked Yorkshire, and spent much of his time at the castle in Thirsk, with his mother. It was she, a few years later, who was moved to help the monks create what became known as Byland Abbey.

So this remote piece of Yorkshire came to be owned by an Abbey over thirty miles away.

As it happened, Fountains Abbey too came to own land in the Nidd valley. Fountains was founded by a breakaway group of Benedictines from York who believed that the life of a monk should not be so easy and pleasant as theirs had become. They felt the need to suffer, so they established themselves in an uncultivated valley a couple of miles west of Ripon. In their first winter they suffered so much that they nearly died of starvation. The following year they decided to join the Cistercian order, and as they began to attract benefactors the Abbey grew and prospered.

Before 1145 one of Roger de Mowbray's men had given the monks of Fountains the village of Dacre, further down the valley, and Roger himself later extended this gift to include large stretches of land southwards and up onto the moor. Unfortunately, he didnt actually own the land to the south of Dacre that he was so generously giving away. It was part of the Honour of Knaresborough, and it stayed that way. To make amends, Roger gave the monks most of the east bank instead, and they bought from him the lands north of Dacre up to the boundary with the Byland estates. The lay-brothers of both houses built granges - small farms - every mile or so up the valley and began to cultivate such arable land as there was, in addition to tending their flocks of sheep.

Mining was a useful source of income for both Abbeys. When he founded Byland, Roger had rather grandly given the monks the rights to "iron ore and a tenth of my lead house ... through all my Forest of Nidderdale", but when Fountains later gained rights over the area round Bewerley, the question arose as to what exactly he had meant. The stage was set for a dispute. It was settled without much of a fight - these were monks, after all. The lead veins in 'Hirefeldberg' - Heathfield Moor - obviously belonged to Byland, whilst those at Coldstones, in Fountains territory, would be worked on a fifty-fifty basis. It was piously agreed that any monk who broke the agreement would go on foot to the other Abbey to apologise, and would be put on bread and water every Friday for a year.

So the people of upper Nidderdale got on with their lives. Each year was much the same as the one before, apart from the occasional unpleasantness like the Black Death of 1349/50. Arriving at the major wool-exporting town of Hull, it swept rapidly up along the rivers to York and Leeds like some malignant tidal bore, and spread on throughout the county. Between a quarter and a half of the population died. Farming communities can't survive the sudden loss of half their workforce, and some farms were simply abandoned. People were forced to leave the area.

One of them was probably Robert of Herefeld. In 1380, thirty years after the first outbreak of plague (and there were several) he was living in the Constabulary of Timble, which included the villages of Fewston and Blubberhouses, ten miles south of where he was presumably born. Along with a few dozen others there, he grudgingly paid his poll-tax of one groat (a coin worth four silver pennies). The king probably needed the money. He had just rewarded a single performance of a dancer from Venice with a gift of 20 marks - that is, with a large bag containing 800 fourpences like these.

The Peasants' Revolt followed a year later. Fletcher called it

... an all-round attempt to throw off the last vestiges of villeinage, on which stress was being laid by harsh or impoverished landlords, just because they were the last vestiges. The poll-tax of 1380 - the third poll-tax in three years and almost the only instance of severe direct taxation that mediaeval England ever knew - no doubt counted for something; but, above all, the peasants decided to throw off a multitude of small and vexatious grievances and petty 'rents in kind' - the two hens at Easter, the dozen eggs at Michaelmas, the fine of fourpence for leave to marry a daughter, the necessity of bringing their corn to the lord's mill to be ground. The destruction of manor rolls and title deeds on which these vexatious little rents were written down, and of the lawyers who enforced them, were avowed objects of the peasants.

When Wat Tyler led the mob to meet the King at Smithfield, and the Mayor knocked him unceremoniously to the ground and killed him, the crowd didn't riot. Instead, they allowed young King Richard to ride forward and tell them that "Tyler was a traitor - I am your leader!" They already knew that. It was the system they wanted to change, not its leadership. They wanted rents fixed at 4d an acre, not at whatever their lord happened to decide it should be that year.

But villeinage was already dying, and within a few years it became normal for wages to be set by the local magistrates in each district.

Once again life returned to normal. Then in 1540 Henry VIII decided that the great monastic houses had grown just too rich to ignore any longer. The area around Heathfield on the west bank of the Nidd, now known as the township of Stonebeck Down, was taken from the monks of Byland and rented out to someone else for £50 a year until a purchaser could be found. A little later Sir Richard Southwell (one of the king's surveyors) bought it outright and immediately sold it on to John Yorke, Esq., of the city of London. The Yorke family owned the land for the next four hundred years.

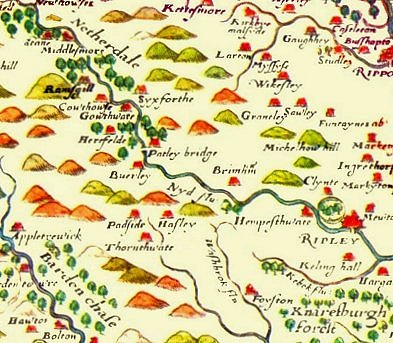

Saxton's 1577 map of the district is a little short on accuracy, but it makes clear that the upper Nidd valley ('Netherdale') - especially the area around Herefelde - was a fertile strip, where hard-working people could grow enough food to live on, with a bit left to spare for the taxman. And just a few miles down-river was the Forest of Knaresborough, a good place to move to when the outlook got too bleak at home.

Spelling of 'Heathfield'

Mediaeval clerks would have been puzzled by our modern insistence that there is only one correct way to spell a word. Since they had taken the trouble to learn to write when most people couldn't be bothered, they felt free to decide on whatever spelling they chose - much as doctors today seem to take pride in their unintelligible prescriptions.

Take for example the village of Heathfield. A.H.Smith in his monumental work The Place-names of the West Riding of Yorkshire traces the evolution of the name through a period spanning 800 years. He says that it originally meant 'open land frequented by jays or magpies' (from higera, feld) and gives the following list of spellings:

| Name | Date | Source |

| Higrefeld, or Higrefelt | 1086 | Domesday Book |

| Hitherfeldebec | c.1175 & c.1200 | Cartulary of Fountains Abbey |

| Hirefeld(e) or Hyrefeld(e) | 1198 | Cartulary of Fountains Abbey |

| Hyrefeldbec | 1260 | Cartulary of Fountains Abbey |

| Hearfield or Hearfeld | 1634,1684,1685 | Deeds belonging to Col. John E.E.Yorke |

| Heathfeld | 1770; 1822 | Col. Yorke; Langdale's Topographical Dictionary |

And there it is. For fifty years in the mid-1600s, the accepted spelling was 'Hearfield'. Or, to be more accurate, a clerk in the employ of Sir John Yorke at the time decided that he would choose to spell the name of the village like this. He could have had no idea of how the consequences of his arbitrary choice would cascade down the years, and still less of how much effort it would take me to track this down.

Yorke bought the land because of the mineral wealth beneath it, and by careful management and judicious investment, he made a great deal of money from it. A sidelight on how well the villagers looked after their lord's property comes from an entry in the Court Rolls of the Manor of Nidderdale dated 28 October 1642 - the opening year of the Civil War.

... that the inhabitants of Hearfield do before the 15th of April next repair and so after cleanse and maintain the water course in Lushey rigg, everyone his part, and so along as the water runneth from the Springhead, upon payne of every part 3s 4d. In 1657, that none shall spoil two standing wells at Hearfield Garth by putting unclean vessels, or such other things, thereinto, upon payne, &c, 4d; in 1675 the inhabitants of Hearfield Pasture are ordered to put their pinfold into good repair, upon payne, &c, of 6s 8d.

'Lushey Rigg' , also known as 'Heathfield Rigg' was a cow pasture shared by at least six farms at Heathfield in 1539.

It's hard to pin down precisely when the name changed. Some inhabitants were calling their village "Hearfield" late in the 18th century. Skipton Parish Records include a baptism on 20 January 1788:

John, son of Joseph Holmes of Eastby, Cotton Weaver, s. of Jonathan H: of Dacre Pasture, Lab'r, and Mary d. of John Stott late of Hearfield in Nidderdale, Taylor.

By then, surnames had become well established, so the migration of the Hearfield family away from their village must have taken place at least two hundred years earlier - probably in the 14th or 15th century.

Yet the evidence is clear. The family name derives from a seventeenth century spelling mistake made by a lead mine owner's clerk.

Nidderdale Rant

And just in case you suspect I'm making it all up as I go along, here's a quote from Bogg's Nidderdale, and the Vale of the Nidd, published around 1890.

An annual feast is held here in the month of September, but is acknowledging in some degree the waning popularity of such things. In its time, however, "the Rant" has been an anniversary with great hold upon the residents of the dale, as well as those who had migrated to other parts of the country, and who made this the occasion of their annual family gathering. Perhaps it will ever remain a season for family re-unions, whatever it may lose of its other features. It will not be inapposite to give here some verses of a dialectical poem from the pen of Mr. Thomas Blackah, a native of Greenhow hill. It will serve the purpose of giving an example of the provincial speech, as well as of affording some reminiscences of these lively times : --

"NIDDERDILL RANT. 1835."

What croods o' foak i' Pateley Toon, / Fra roond an' square, beeath up an' doon

All starin' -see 'em!

Thar's ivvery shap and ivvery mak, / Beath gert an' lile, beath white an' black,

Wal ivvery street an' ivvery track, / Is block'd up wi' 'em.

Fra t'Reeaven Nest, an t'Middle-toon, / Fra t'Steanbeck Up an Steanbeck Doon,

An' fra t'Hoalboddom ;

Ramsgill an t'Wath, ther quota send, / Harcasle youths i' drooves attend,

Sike lots fra Greenha an t'West End / T'toon winnot hod 'em.

Oade men 'ats' fowerscoore summers seen' / Wi' hairless heeads an' sparkless een,

Cum toddlin thither :

Thar's lots ov barns at just can woak, / I' brats an' frocks as white as choak,

An' fulgrown lads an' lasses stawk / Aboot togither.

A hunderd different voices rise, / Sitch bawlin, hooarse, discoordant cries,

A preist wad maddle ;

Greengrocer Jamie praised his fruit, / Nut Harry tried to follow suit.

An' Dicky Dee bowt fer his brute, / A brand new saddle.

Ower t'Brig they gan be'y scoors at yance, / To Bewerley Park to watch 'em dance,

An' lake at creckit ;

Thar's kissing rings, an' twos an' threes, / They skip and jump aboot like fleas;

T'Victoria Band maks under t' trees / A bonny racket.

Neea matter hoo wer time we spend, / Thar's ne'er a day bud what mun end,

Time keeps advancin

At Feeast 'ir fast it moves away, / An' monny a yan were thar that day,

At winnot (ah'll be bun to say), / T'next Feeast be'y dancin.

They toke c' Feasts, Wakes, Tides, an' Fairs, / Whar graceless lads up't streets i' pairs,

T'yung lasses follow

Begin an' lait all Yorkshire throo, / An' then yeel finn'd my words cum true,

At Pateley Feeast a'll quite ootdew, / All t'others hollo,

Fra ivvery part o't Deeal they're tharr. / 'Tween Darley Beck an' Haden Carr,

An't Covil Hooses ;

Girt stridin' chaps c' milk weel fed, / Like Bewerley Bill an' Hearfield Ned,

'At's used to nowt bud wark an' bed, / An' wile carooses.

Strang lasses cum frat' Folly Gill, / Heights, Thornfert, an Hardisty Hill,

Wi' reudy feeases ;

Fra t'Smeltas, Wilsil, an' New York, / I' 'lastic boots weel heel'd wi' cork,

Seea pleeased this day to miss ther wark, / Fer t'seeak a't reeaces.

Whar yance t'bold Roman Eagle flew, / Noo floatin see t'red white, an' blue,

Freedam's gay standard;

Fra Knaresbro' Harrogate, an' Leeds, / Pair efter pair to Guyscliff speeds,

Whar Mowbray's noble prancing steeds / Lang sin had wandered.

Wi' joyous smiles as neet drew on, / They start i' droaves (nut yan be'y yan),

Doon t'streets to straddle:

Thar's monny a lass wokes street art' brant / An' at her sweetheart leaks aslant,

As arm i' arm fra Pateley Rant, / They heeameward paddle.

I wish I'd been there. I'd have enjoyed talking to Hearfield Ned.

Source notes

- Yorkshire - Byland, 1815

- Upper Nidderdale - Speight, 1906

- The Striding Dales - Sutcliffe, 1929;

- Nidderdale and the garden of the Nidd - Speight, 1894

- Byland Abbey - Peers (HMSO), 1952

- Nidderdale from Nun Monkton to Whernside - Speight, 1906

- An historical topographical and descriptive sketch of the valley of the Nidd - Grainge, 1863

- Anglo-Saxon England - Stenton, 1971

- http://www.mowfam.freeserve.co.uk

- Fountains Abbey - Gilyard-Beer (HMSO), 1970

- A history of Nidderdale - Jennings (ed), 1983

- Lays and leaves of the Forest - Parkinson, 1882

- English wayfaring life in the Middle Ages - Jusserand, 1889

- An introductory history of England, Vol 1 - Fletcher, 1910

- The Place-names of the West Riding of Yorkshire - Part 5 - A.H.Smith, 1956-7

- Upper Nidderdale - Speight, 1906

Unexpected levitation is just one of Nidderdale's many delights.