The background to this story, concerning street cleaning and domestic waste, the Borough Scavenger, and the monarchs involved, is in Part 1. This establishes quite clearly that common sewers were for rainwater and house ‘grey’ water, and that the collection and removal of domestic sewage was definitely the smelly responsibility of the probably smelly householder.

Here in Part 2, I concentrate on the building of a new common sewer in one of the posher parts of London – Pall Mall. The facts in this story come entirely from contemporary newspaper reports, which I came across quite by accident when researching cowkeepers from Swaledale - the internet is a very beguiling device.

Setting the scene

This illustration, much reduced in size, is from London in 1880 by Herbert Fry and although most of its buildings are much later than 1730 it clearly shows the relationship between the key places in this story: Pall Mall, The Mall, St James’ Palace (then the main official residence of the monarch) and Buckingham House (re-furbished as Buckingham Palace, and moved into, by George II). Nelson’s column and Trafalgar Square in the foreground were of course still in the future.

Formerly an open park, Pall Mall was laid out as a residential street in 1661. Its proximity to St James’s Palace, built by Henry VIII and again a royal residence after the Restoration, had made it prime real estate and it quickly filled up with posh houses and gentlemen’s clubs. Or so I thought.

Formerly an open park, Pall Mall was laid out as a residential street in 1661. Its proximity to St James’s Palace, built by Henry VIII and again a royal residence after the Restoration, had made it prime real estate and it quickly filled up with posh houses and gentlemen’s clubs. Or so I thought.

Then I came across the 1694 list of residents required to pay the 20% tax raised for King William’s war with France, and the most frequent rental value in Pall Mall then was £8-10 pa, which does not seem excessive. Parts of the South side of Pall Mall were posh. The Countess of Portland was hit hardest, with a £300 tax on her property. The other titled residents of the South side obviously had better accountants, and paid half that, or less. The biggest difference between North (84 taxpayers altogether) and South (82) sides was the value of their other investments, and twice as many South-siders had to pay a further tax of £200 or more. Nell Gwynn, one of the many mistresses of Charles II and mother of the Duke of St Albans, had lived along here, handy for the Palace. Silversmiths and shopkeepers lived here too. The posh gentlemen’s clubs came a century later.

The sketch in a zoomable format can be seen in an analysis of Sherlock Holmes' novels.

In 1662 the new Pall Mall was placed under the control of Paving Commissioners, including the Earl of St Albans (no relation to the aforementioned illegitimate Duke, who was born in 1670). The existing landowners, including the Earl of St Albans, were extremely annoyed that they had built their houses facing the old Mall - now called The Mall - which led to the Queen’s Palace (aka Buckingham House but not yet an official residence) and these houses were now the wrong way round. They petitioned the King in 1664 to say that their houses could not be turned ‘without great damage and charge’ and could they please have the old road ‘to augment their gardens’. He agreed. He also made sure, in a specific mention in his Act of 1662, that the new householders of Pall Mall were quickly taxed at the rate of ‘sixteene pence for every square yard [between the frontage of] every dwelling House Yards or Gardens and the middle of the High way or Street’ so that the Paving Commissioners could buy ‘new Stones and Gravell’.

The Commissioners of Sewers

When Queen Anne came to the throne after the death of William of Orange, one of the early pieces of legislation she signed (in 1709) closed a loophole. Every householder was expected to pay the Commission for any work done in front of their house - above or below ground - and was assessed accordingly. The payment due to the Commissioners had been based on the householder's wealth but the assessment had not included the value of any copyhold or customary lands he owned. This amendment allowed the Commissioners to seize these lands from a defaulting householder if necessary, and take over any of the income generated. You can tell they were serious about being paid.

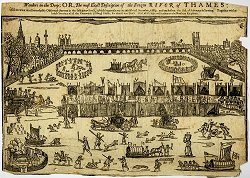

1709 was also one of the years when the Thames froze (this engraving is at the British Museum; the old London Bridge, with its houses and shops, is in the background). There were instant fairgrounds and market stalls and, no doubt, impromptu ice hockey matches. It is difficult now to decide whether this extreme cold weather - some called it the Little Ice Age - helped or hindered the Commissioners, but it certainly helped the local population get across the river quickly, on foot or in a carriage, and probably helped keep the smell down.

1709 was also one of the years when the Thames froze (this engraving is at the British Museum; the old London Bridge, with its houses and shops, is in the background). There were instant fairgrounds and market stalls and, no doubt, impromptu ice hockey matches. It is difficult now to decide whether this extreme cold weather - some called it the Little Ice Age - helped or hindered the Commissioners, but it certainly helped the local population get across the river quickly, on foot or in a carriage, and probably helped keep the smell down.

The Commissioners had been in existence since at least 1532. They operated all over the city and were always involved in new building works. Their records show that in 1599, houses built on the site of the old playhouse at Newington, south of the river, were joined to a common sewer.

And in 1634 the Commissioners gave the problem of the smelly Moor Ditch to Inigo Jones, who suggested the construction of a vaulted sewer to the Thames ‘of 4' breadth at bottom, and 6' at least in height’ and, significantly, that the old ditch be filled up with earth and no building be allowed on it.

The Commissioners continued, plodding from crisis to crisis and keeping notes. In The Law of Land Drainage and Sewers Kennedy and Sandars listed the names of all the Commissioners for Westminster and part of Middlesex, as at June 1776. The list starts with the Lord Chancellor, then goes on to itemise the Dukes of Beaufort, Marlborough, Portland, Manchester, Newcastle, Northumberland, and Devonshire, then 35 mixed Earls, Lords and Viscounts and a further 142 Knights, Honourables, and plain Esquires. No wonder all the legislation said that decisions could be made ‘by any Six or Seven of the Commissioners’!

The Commissioners continued, plodding from crisis to crisis and keeping notes. In The Law of Land Drainage and Sewers Kennedy and Sandars listed the names of all the Commissioners for Westminster and part of Middlesex, as at June 1776. The list starts with the Lord Chancellor, then goes on to itemise the Dukes of Beaufort, Marlborough, Portland, Manchester, Newcastle, Northumberland, and Devonshire, then 35 mixed Earls, Lords and Viscounts and a further 142 Knights, Honourables, and plain Esquires. No wonder all the legislation said that decisions could be made ‘by any Six or Seven of the Commissioners’!

This sketch of the 2nd Earl Bathurst is at the National Portrait Gallery. I include him here not only because was he Lord Chancellor in 1776, and therefore the Chief Commissioner for Sewers, but because Dr John Bathurst, physician to Oliver Cromwell, had bought the North Riding manor of Arkengarthdale in 1635 and started the lead mine there. His grandson even has the local pub named after him. This is a pleasing link back to my Swaledale research but I have not been able to find a close link between the two family trees, although it ought to be there somewhere.

The Law of Land Drainage and Sewers also included a ‘List of the SEVERAL SEWERS under the Jurisdiction of the Commissioners for Westminster, and part of Middlesex’. Some of them led to adjacent sewers; some emptied into the Thames. There were not very many of them. Their start and end points were:

- King’s Scholars Pond: Marylebone High Street to Mr Adam’s Wharf at Milbank

- Hartshorn Lane: Rope Walk (Marylebone) to Northumberland Street

- Pall Mall: Silver Street (St James) to Scotland Yard

- Essex Street: Holborn (Bloomsbury) to Essex Street

- Durham Yard: Drury Lane to the Adelphi

- Carey street: Portugal Row (Lincoln’s Inn Fields) to Chancery Lane

- Somerset Watergate: Catherine Street (Strand) to Somerset House

- King Street: Downing Street to Chanell Row

- College Street: James Street (Pimlico) to Millbank near Abingdon Buildings

- Wood Street: Duck Lane to Mr Pearce’s Brewhouse at Millbank

- Romney Row: Horseferry Road to the Horse Ferry

- Strand Lane: Holywell Street (Strand) to the bottom of Strand Lane.

The south side of Pall Mall remained crown property, and royal rights also involved royal responsibilities, which included flushing out the drains. I do not imagine for a minute that Queen Anne tucked her skirts into her drawers and got out a brush, but the Treasurer of the Chamber included the following payment in his 1710 Civil List’s Household accounts:

‘To Langley Bradley for looking after the clock in Scotland Yard, and Thomas Herbert for looking after the clocks of all her Majesty's Palaces, lighting the lamp in Scotland Yard, cleaning the main sewer from the sluce in the Park down to the lower end of the Dock in Scotland Yard: £51 14s 6d.’

In 1728, a new church – St John’s – was built at Smith Square just off the riverside at Millbank and within St Margaret’s parish. This was part of the provision of new churches after the Great Fire, paid for out of that coal tax (see Part 1) and it became a drainy problem. The Church Commissioners received a complaint from a Mr Devall and others, of St Margaret’s

parish, that there was no room to make a sewer to carry waste water from their houses because of a drain made for the church. The Commissioners subsequently gave permission for Mr Devall to join his house to the church’s drain.

parish, that there was no room to make a sewer to carry waste water from their houses because of a drain made for the church. The Commissioners subsequently gave permission for Mr Devall to join his house to the church’s drain.

To my great delight, that 1694 list of taxable residents in Pall Mall North (also in St Margaret’s parish) had included a Mr Nicholas Devall: could it be the same man? Well, possibly, but he must have moved because Noorthouk's 1770 map shows it’s just too far.

However, from the number of references (764, count them) to “sewer OR drain” on British History Online it is beginning to look as if 17thC and early 18thC house builders built their own sewers, or linked to the nearest one, or covered up smelly ones crossing their back gardens. All they needed was permission from the Commissioners of Sewers, who positively encouraged individuals to spend as much of their own money as they wished. In 1691 one houseowner got a refund from the Commissioners when new neighbours joined into the sewer he had built from his house in Golden Square to the common sewer at Lower James Street. But such ad hoc provision could not provide the robust kind of drainage now needed.

The Pall Mall sewer

On 23rd May 1729, the Daily Journal printed this request for tenders:

‘‘The Commissioners of Sewers for Westminster, having resolved to make a new Sewer from the Gate of Middle Scotland-Yard, up by Charing-Cross, thro’ Pall-Mall, to the Wall of St James’s-Park, do hereby give Notice, That they will receive Proposals from Diggers, Bricklayers, Carpenters, and Paviors, in Writing, Sealed up, for doing the same, on Friday the 30th of this Instant May, at 10 o’clock in the Forenoon, at the Town Court House near Westminster-Hall. [See] Mr Nash, Clerk, at his house in Castle Street for blank proposal [forms].’

By 1729 the monarch was George II and he was particularly inconvenienced by the new Pall Mall sewer. I do wonder if the timing was accidentally-on-purpose. Like his German-speaking father before him, this recently-crowned king was not popular.

Once work had started, follow-up reports in many papers said that this new sewer would cost £6,000 ‘which is to be defray’d by the Ground Landlords’. Presumably this means the actual land owners rather than any on-site tenants or lease-holders.

Since Pall Mall had been developed in the 1660s it is possible that the new sewer was a replacement all the way along; the report of 9th October quoted below mentions an earlier conduit at Cleveland Row. Many newspaper reports imply that the Pall Mall sewer joined an earlier sewer from the Haymarket to the river, which was subsequently not big enough.

Here is a 1790 map, which I have marked with the route and with the places mentioned in the newspaper reports. Since work started at the output end (No 1 = the Thames) the highest number is at the start of the sewer:

| 9 | from the Stable Yard into St James's St | 4 | turn from Cockspur Street into Charing Cross |

| 8 | turn at Cleveland Row | 3 | down Whitehall then through the narrow gate into Middle Scotland Yard |

| 7 | along the whole length of Pall Mall | 2 | across Middle Scotland Yard |

| 6 | along Cockspur St, past the end of the Haymarket | 1 | to the outlet at the wharf |

| 5 | along Cockspur St, past the bottom of Suffolk St | 1 | into the Thames (muddy brown, far right) |

The places mentioned in the newspaper reports which follow are:

| A | the Admiralty | J | St James's House (or Palace) |

| C | the Cocoa Tree Chocolate House (a notorious meeting place for gossip and Tory politics) | M | The Mall - at the westerly end of which is what we now call Buckingham Palace |

| H | Hungerford market and sewer | T | Mr Chevenix's celebrated toy shop and theatre ticket office |

The narrow gate into Whitehall from Middle Scotland Yard (only 10' wide, which caused great difficulty) was just opposite the Admiralty in Whitehall. An old sewer apparently followed a very similar route, at least from the Haymarket to the Thames. This also caused great difficulties, as you will see.

Work starts in July 1729

There is a record in the Calendar of Treasury Papers [British History Online] of a petition in December 1728 by wharfingers Phillip Farewell and Richard Moore. They were sub-tenants of the Duke of Chandos, occupying a piece of land in Middle Scotland Yard, which adjoined the river Thames. They complained that in October last (1728) the wharf was broken up to make a drain and they had lost both their business and their customers. The heartless judgement was that ‘it was a common sewer and the inconvenience must be submitted to.’ Had work already started? The interruption cannot have been permanent because in 1741 there was a petition to the Treasury from the Duke of Chandos for an extension to the lease for the wharf and buildings in Middle Scotland Yard. I hope that Messrs Farewell & Moore’s business survived.

Work on the narrow Charing Cross to Whitehall section started on the 2nd July 1729 and several newspapers carried the warning that the road would be closed to all coaches, carts and carriages for about six or eight days. Of course someone had to have a go, and

‘On Tuesday Night a Hackney Coachman carelessly drove his Coach and Horses into the Trench against Will’s Coffee house at Scotland-Yard Gate, which is digging for the new Sewer from St James’s Stable-Yard to Scotland-Yard, tho’ without any Damage either to the Driver or Horses; but to prevent the like Accidents, it was Yesterday inclosed.’

The newspapers of the time carried few illustrations. To make some sense of the story, here are two drawings of the major sewer works in Fleet Street in 1845, first published in the Illustrated London News in October of that year. The first shows a cross-section (see how deep the workmen are); the second shows how inconvenient it was for everyone else.

The newspapers of the time carried few illustrations. To make some sense of the story, here are two drawings of the major sewer works in Fleet Street in 1845, first published in the Illustrated London News in October of that year. The first shows a cross-section (see how deep the workmen are); the second shows how inconvenient it was for everyone else.

Since the 1729 newspaper announcement asked for tenders from diggers, bricklayers, carpenters and paviors, I think that the method would have been very similar, with timber shuttering holding back the sides of the trench, whilst the sewer pipe is built at a depth of at least 20' (see 27th Sept) and side-sewers are joined in from adjacent streets and houses. The dug-out earth was finally replaced, and the road surface made good again by the paviors.

So how was the Pall Mall sewer actually built? I could find very few clues. In 1720 the open Tyburn Brook was ‘arched and covered over’ by bricklayer Henry Avery during the development of the nearby Grosvenor estate, but this was work at ground level. The 9th October report describes the Pall Mall bricklayer as ‘paving the bottom of the sewer’ as if another material would be used for the rest.

The big bucket on the left of this second picture looks as if it ought to be part of a yellow digger driven by a cheerful builder called Bob, and just beyond it are what look like pre-cast curved sections which might be for the sewer itself – so I suspect that technology had moved on a bit since 1729. There are many references to sewer repair and build on British History Online but irritatingly few mentions of the materials used. However, the description of the Bedford Estate (Survey of London) says that in 1633, specifically for rainwater removal:

The big bucket on the left of this second picture looks as if it ought to be part of a yellow digger driven by a cheerful builder called Bob, and just beyond it are what look like pre-cast curved sections which might be for the sewer itself – so I suspect that technology had moved on a bit since 1729. There are many references to sewer repair and build on British History Online but irritatingly few mentions of the materials used. However, the description of the Bedford Estate (Survey of London) says that in 1633, specifically for rainwater removal:

‘the Earl of Bedford's articles of agreement with the builders in Covent Garden had been remarkably specific. Brick sewers were to be built along the forefronts of each plot, below the level of the house cellars, 4 feet in height, 2½ feet in breadth at the shoulders and 1 foot 3 inches wide at the bottom. They were to be so contrived that they carried away the surface water and were to slope into the main sewer, the construction of which was to be the Earl's responsibility.’

This is a very clear description, although it implies that the main sewer was also to be the Earl’s responsibility, and there is no specification here for that. And a height of 4' seems over-generous for rainwater - although I read elsewhere of the need for the cleaner to be able to get inside. But the use of bricks is unambiguous, as is the intention not to flood the cellars. In 1670, similar brick sewers were specified for new houses being built in Leicester Square. So it seems that the Pall Mall sewer would also be built of brick but I would be delighted to hear from anyone who knows more.

Back in Pall Mall, very early on twenty workmen narrowly escaped when ‘Holdfasts and Props gave way’ at one point and the sides fell in, ‘to the possible danger of neighbouring houses’.

![]() Permission was given for the Lords of the Treasury (on the wrong side of the roadworks in Whitehall) to pass through St James’s Park in their coaches whilst the road was closed. Presumably other commuters had to find a different detour.

Permission was given for the Lords of the Treasury (on the wrong side of the roadworks in Whitehall) to pass through St James’s Park in their coaches whilst the road was closed. Presumably other commuters had to find a different detour.

By the 19th July, the papers were reporting that the contractors had to complete work by the 24th October, or pay a penalty of £2,000.

One damn thing after another

On the 25th July was a report that

‘Last Night great Part of the Sewer ... fell in near the Globe-Tavern in the Haymarket, to the great Terror of the Inhabitants, who kept a Watch all Night to prevent any mischievous Consequences.’

More accidents and collapses happened: one workman’s arm was broken, another was ‘almost engulfed’, the contractors had to pay £150 for house damage. In August, the papers reported that the collapses caused by ‘great rains which have fallen’ could mean that the sewer would not be completed this year.

On the 16th it was reported that the Commissioners had ordered that the workmen must make good that section of the sewer already started, before breaking new ground in Pall Mall.

On the 16th it was reported that the Commissioners had ordered that the workmen must make good that section of the sewer already started, before breaking new ground in Pall Mall.

But by the 25th, the weather having improved, everyone was optimistic again and promising that not only would the sewer be complete, but also the bridge from Fulham to Putney, thanks to the famous Engine Pumps of Mr Gray, Engine-maker at Mill Bank, Westminster. Mr Gray would have been well aware of Mr Newcomen’s newly-developed and equally famous pump. Newcomen died in 1729 but he would have died knowing the difference that his pumps would make in the civil engineering and mining industries in the future.

On the 4th September the old sewer adjoining the new one collapsed and flooded the new works at Suffolk Street. The Daily Post of 6th September reported (and here I leave unchanged the printer's exasperating use of ‘f’ for ‘s’):

‘Yefterday Morning about two o’Clock, the Inhabitants of the lower Haymarket were call’d out of their Beds, fuch vaft Quantities of Earth having fallen into the Sewer that greatly endanger’d the Foundations of the Houfes, fome of which ‘twas expected every Minute would fall. The York Buildings Company’s Main Water-Pipe was again broke, and many Cellars, which had great Stocks of Wines, Brandies, &c. in them, were laid under Water, and very great Damages done; and if a Man, who at the hazard of his Life, had not been let down with Ropes about his Body and ftopt the Pipe, the whole Neighbourhood had been ftill much greater Sufferers. When the Ground firft fell in the Houfes near it fhook as if an Earthquake had happen’d, which ftruck the Inhabitants with the greateft Terror and Confternation.’

Two weeks later more heavy rain again broke through into the new sewer from the old and on its way flooded Mr Chover’s Wine Vault a second time. The sewer in Pall Mall collapsed, and the foundations of the ‘great Toyshop at Suffolk Street, Charing Cross, gave Way in such a Manner as greatly alarm’d the Family’. Workmen, despite the continuing rain, had to fill up the sewer to prevent further collapses.

This is a picture of Cockspur Street, which joins Charing Cross to the Mall, and off which Haymarket and Suffolk Street branch to the north. The shadows suggest that the sunlit buildings are facing south; so Mr and Mrs Chevenix, the unfortunate toy shop owners, lived on one of the corners. (Thornbury).

This is a picture of Cockspur Street, which joins Charing Cross to the Mall, and off which Haymarket and Suffolk Street branch to the north. The shadows suggest that the sunlit buildings are facing south; so Mr and Mrs Chevenix, the unfortunate toy shop owners, lived on one of the corners. (Thornbury).

The Daily Journal said the vaults of the King’s Arm Tavern in Pall Mall were so overwhelmed by the quantity of water flowing into them from the new common sewer that the landlord had to employ labourers constantly to throw the water out, then to send for the Engine from St James’s Square to empty them of between 4 and 5 feet of water. The London Journal reported that the Engine moved 150 tons of water in eight hours.

Here is an indication of the depth of the digging work: on 27th September 1729 the Universal Spectator and Weekly Journal reports that:

‘Thurfday Morning a Servant to Mr Scawen, of St James’s Square, riding too near the Sewer at the End of Suffolk-Street, Charing Crofs, the Horfe took a fudden ftart, and fell about twenty five Foot deep into the Earth amongft the Diggers, without doing them or himfelf any Hurt; the Rider having the good Fortune to quit the Horfe in Time.”

On the 2nd October, the Daily Post reported that it was much doubted whether the Court would remove from Kensington to St James until after the King’s birthday (on the 30th), ‘there being no Conveniency for the Passage of the Coaches’ due to the sewer not being finished, and that orders had been given (by the Commissioners? or the Palace?) that the Pall Mall work must be finished in a fortnight’s time, ‘for the nobility to have open passage to the Court’. On the 7th October the Earl of Grantham, Lord Chamberlain of Her Majesty’s Household, went to examine the state of the sewer.

On Thursday 9th October the new sewer fell in by the Duke of Bridgwater’s at Cleveland Row, right on the corner of Pall Mall and St James’s Street, and killed John Pyke (or William, according to another paper) a bricklayer paving the bottom of the sewer; broke another’s arm, and a labourer’s back. The accidents happened as the workers were digging under some existing wooden pipes, since they neglected to shore up the ground. On the 18th, orders were given that no more ground should be broken because His Majesty intends to come and reside at St James’s on the 24th. On the 23rd, the Court deferred the move until next Tuesday, ‘the Rains having hinder’d the closing of the sewer near St James’s House’. Poor William (or John) Pike ‘not yet 20’, made it into the summary of Diseases, Casualties, Christenings and Burials published every week in all the London papers, as one of three people killed that week.

At 6.30pm on Friday, 24th October, the programme for an open-air lecture at the corner of Lincoln’s Inn Fields (pictured left) included: ‘the Common Sewer, how deep?’ as well as stories concerning ‘a Bundle taken from an empty House’ and ‘two Fools well met’, which suggests that it was common for someone to pass on local news and tell stories to people who could not read the newspapers (although someone would have to read them the advert for the lecture, of course).

At 6.30pm on Friday, 24th October, the programme for an open-air lecture at the corner of Lincoln’s Inn Fields (pictured left) included: ‘the Common Sewer, how deep?’ as well as stories concerning ‘a Bundle taken from an empty House’ and ‘two Fools well met’, which suggests that it was common for someone to pass on local news and tell stories to people who could not read the newspapers (although someone would have to read them the advert for the lecture, of course).

On November 19th, the contractors were ordered to stop work until next year, and make good the road in time for the opening of Parliament.

On 24th January 1730 the Commissioners paid the contractors £3,000.

Work completed September 1730

By July 1730, work must have resumed because the Weekly Journal reported yet another collapse of the Old Sewer into the New Work at the lower end of Pall-mall. Then the Evening Post reported that the ‘great Undertaking’ of making the new Common Sewer from Scotland-Yard to Cleaveland-Court at St James’s would be finished on the Saturday (15th August). Saturday’s papers said: the work will be finished ‘in a few Days’. But it seems that it was just the Pall Mall section which was finished, because early in September there were reports that ground breaking had started in Cleveland-Court but that there was no doubt it would be finished before the Court needed to move to St James’s.

On Thursday 10th September, the Grub Street Journal reported 'Yesterday the new Sewer was completely finished from Scotland-yard gate to the Stable-yard, St James’s.'

A few months later, the Daily Journal of 18th January 1731, reported:

‘We hear the Persons concerned in that great Undertaking, in making the New Common-Sewer in Pall-Mall, which was so carefully and expeditiously perform’d, are treating with the Commissioners for rebuilding the Parish Church of St Giles’s.’

How short people's memories are; someone’s PR department has clearly been at work.

But that wasn’t the last mention in the newspapers. On 19th June 1731 Reed’s Weekly Journal reported that

‘The new Sewer leading from Scotland-Yard to the Stable-Yard Gate St James’s was last Thursday stopped [blocked], occasioned by the late Rains, insomuch that Cleaveland-Court by St James’s lay last Thursday Night several Foot deep in Water.’

And on the 23rd July the sewer near the Cocoa-Tree Chocolate House on the north side of Pall Mall fell in and Sir Jeremy Sambroke’s Coach had the Misfortune to fall in with it.

the Cocoa Tree Chocolate House

By now, the inhabitants of Pall Mall were refusing to pay their assessments for the new sewer and 'several law suits are likely to commence'. The heap of soil which had to be moved to enable a repair, and which itself then fell onto the Cocoa-Tree, was ‘upwards of 100-waggon-loads’.

On 21st August 1731, Fog’s Weekly Journal reported that

‘Last Wednesday Mr Dagley and Mr Wells, Bricklayers, and Mr Porter, Carpenter, began to survey the new Sewer which was lately built from Scotland-Yard to Cleveland Court, St James’s. They found several Defects in the said Sewer, which will we hear cause a great Part to be broke up again. They were employ’d on one part by the Ground Landlords, who are obliged to pay for the Building of it, and on the other part by Order of the Commissioners of the Sewers.’

And then the newspapers, or at least those available through the Gale website, went quiet. There was a report of the Fleet Street sewer falling in after a great Shower of Rain, in August 1732. The Pall Mall repairs must have been completed, because in October two men who were cleaning the sewer under Hungerford Market (on the other side of Charing Cross) were unable to get back to street level because of the fast-flowing tide. Fortunately they had lights with them so they went up as far as the middle of Pall-Mall (having been nearly four hours underground and almost suffocated) and

‘hallooed at a Gully-hole, and allarmed feveral People in the Street, who immediately came to their Affiftance, and with much Difficulty they were got out’.

In September 1733, the London Gazette reported that the next big Sewer project had just been announced, to convert the Fleet river to a covered sewer between Holborn Bridge and Fleet Bridge.

Other drainy stories of the time

Newspaper articles 1721-34

The Daily Courant (London, 6th May 1721):

‘Whereas at the last Sessions of Oyer and Terminer held at Hicks’s Hall, one Bentley was by Order of the Commissioners of Sewers for the said City and Liberty of Westminster ... prosecuted for shooting Night Soil into a Grate over the Common Sewer in the Broad-Way in the Parish of St Giles in the Fields; and being thereof Convicted, was sentenced to be whipt from White-Hart Corner in the said Parish to St Giles’s Pound, which sentence was accordingly executed upon him. Now the said Commissioners do hereby give this Publick Notice, in order to deter all other Persons from the like pernicious Practice for the future; and do further promise a Reward of Ten Shillings to any Watchman or other Person, who shall discover any Person committing the like Offence within the Jurisdiction of the said Commissioners, to be paid upon Conviction, by John Nash in Castle-Street above the King’s Mewse, Clerk to the said Commissioners.’

The London Journal (Saturday 21st September 1723):

‘One Philip Stock, a Bailiff’s Follower, hath been lately disciplin’d by them, being plunged several times in the Common Sewer [presumably still an open ditch], and obliged to drink of that nasty Water. Another of the same Profession, by the Hurt he got there, died a few Days ago in St Thomas’s Hospital.’

Probably because they would not be difficult to find, sewers were used as a means of direction: a 1724 advertisement of an auction directed would-be buyers to come to ‘the 3 Tun Yard against the Pump and near the common Sewer in Crutched Friars’. This auction, by the way, was described as a Sale by the Candle, which I had not heard of before. Apparently a pin was put on a candle and bidding continued until the pin fell out, at which point the item went to the most recent bidder. Since whole ships, or their contents, were often the subject of a Candle auction, last-minute bidding must have been intense.

The Flying Post (5th April 1729):

‘The Commissioners of Sewers at a Publick Meeting at Guildhall, fin’d the Scavenger of St Bride’s, and the four Scavengers of Cripplegate, for not keeping the Streets clean; which Fines are paid into the Chamber of London, and apply’d towards repairing and Cleaning the several Sewers in the City.’

And this witty but nasty extract from Prompter (13th December 1734) completes my unsavoury essay.

‘As I was walking near Marybone-Fields, by the Edge of one of those Publick Repositories, where they store up the Spare-weath of this abounding Metropolis, my Nose took Alarm at the Fragrancy; and furnished my Fancy with a Notion that it was a Use not Unlike This to which the French have converted our Theatres...

... I was interrupted in my Cogitations by the Approach of a Covey of Stragglers from Westminster School [pictured left] with the Spirit of the Place in their Faces. One of These was pressing an Apple, with his Left Hand, upon a Cowkeeper’s Boy they had met with, while he held conceal’d, in his Right, a short Piece of Lathe enrich’d at one End by the Spoils of the Lake it had newly been dipp’d in. The profer’d Apple was rejected with suspicious and averted Frownings [until] the boy roar’d out I won’t I won’t with a Mouth as Round as the Apple. In that critical Moment, the persisting Benefactor produc’d the Lathe from behind his Coat, and drawing the Fullness of its Treasure quite cross the Protestor’s Mouth, told him It was Every Man to his Palate.’

I hope that by now you know exactly what he was talking about.

Bibliography and Links

This bibliography is for both Part 1 and Part 2.

The newspaper cuttings are my own transcripts from the Burney Collection, which is partly digitised and available online. Much of the non-newspaper information in this essay came from books and papers stored on British History Online. This enormous website goes into great detail and is an engaging read on a snowy weekend. Other references are:

Websites

Because of the many public sources used in this essay, I have put more links than I otherwise would to the relevant websites. I realise there is a risk that a website might move or close; please let me know if you notice this has happened.

- Links to and transcripts from British History Online are made under their terms of use, which give permission from the University of London and The History of Parliament Trust for such extracts only to be made for personal and non-commercial use.

- Digitised images of a selection of newspapers are available from the British Library.

- The Lancashire County Council Libraries website give free online access to the Gale site to any library member, as do some others (a UK address is all you need to join; check your own county library first).

- The 1671 Act of Common Council for Paving and Cleansing the Streets is on British History Online.

- A very detailed (house by house) map of 18thC London is the Horwood map.

- And here is another link to a very good zoomable 1770 map at the British Library.

- The City of London collection Collage contains some wonderful historical images and maps.

- Mary Gayman’s three essays on the history of London sewers give a very entertaining if aromatic and occasionally explosive picture of why and how they were built.

- A clear and brief history of this part of the West End, and a series of wonderful illustrations of the original buildings, including the Cocoa Tree – floor plans and cross-sections sometimes included - is provided by the Survey of London under the sponsorship of English Heritage. The survey is reproduced on British History Online.

- Early Victorian housing and drainage, and much more, are described in Lee Jackson’s Victorian Dictionary.

- The history of British newspapers describes early news pamphlets and daily newspapers.

- London’s early water supply is explained here and the archivist at Thames Water rummaged helpfully but unsuccessfully for information about 18thC drain-building materials.

Books and articles

- Baker, T F T (Ed) A History of the County of Middlesex 1998, (British History Online)

- Baldwin, Latham, Sanitary Engineering: A Guide to the Construction of Works of Sewerage and House Drainage : with Tables for Facilitating the Calculations of the Engineer, E. & F.N. Spon, 1878 (Google books)

- Boulton, Jeremy, Neighbourhood and Society; Southwark in the 17thC, Cambridge University Press, 1995, (Google Books)

- Cockayne, Emily, Hubbub, Yale University Press, London, 2007: a scholarly and funny thesis on all types of nuisance in the 17th and 18th centuries

- Eveleigh, David J, Bogs, Baths & Basins, Sutton Publishing, 2002: set more in the 18th and 19th centuries

- Franklin, Benjamin, Autobiography, Project Gutenberg

- Keene, Derek; Earle, Peter; Spence, Craig; Barnes, Janet, Four Shillings in the Pound, 1992 (British History Online)

- Kennedy, G G & Sandars, J S, Land Drainage & Sewers, London: Waterlow Bros & Layton, 1884 (my impressed thanks go to the ingenious Norwich librarian who identified the online extract).

- Noorthouck, John, A New History of London, 1773 (British History Online)

- Skempton, Prof Sir Alec (Ed), Biographical Dictionary of Civil Engineers Vol 1, Thomas Telford, 2002 (Google Books)

- Thomas Duncan A & Ford Roger R, The Crisis of Innovation in Water and Waste Water, Edward Elgar Publishing, 2005 (Google Books)

- Thornbury, Walter and Walford, Edward, Old and New London, 1878 (British History Online)

- Walford, Edward, Greater London, Cassell & Co, 1883 (British History Online)